Graham Linehan in Handcuffs

Warning That Britain’s Laws Have Broken Free from Reason

When the spectre of authoritarianism is raised today, there is a tendency for us Brits to look outward: To America, which is accused of sliding toward dictatorship, France who, we are told, is flirting with illiberal populism and Germany which is guilty of resurrecting dark ghosts from its past. Yet the United Kingdom, once celebrated as the cradle of constitutional liberty, is already walking a perilous path. Granted, this transformation is not as overtly evident as it would be if soldiers were lining the streets. Instead, it unfolds through the slow withdrawal of democratic norms, the expansion of state power into cultural domains, and the adoption of laws so ambiguous that personal offence becomes the fuel for criminal charges.

Historian Dr. David Starkey has cataloged a series of cumulative shifts that have reshaped the British state. He points to the constitutional revolution under New Labour, where the model of “parliamentary sovereignty” was hollowed out. The authority of Parliament, the living expression of the people's consent, was diluted by external legal structures and bureaucratic layers, displacing the ancient arrangement in which law was integrally British rather than imported.

Starkey also shines a light on the unprecedented scale of immigration since 1997. He contends that New Labour’s mass-immigration campaign, far beyond any previous population movement in British history, even exceeding the Roman or Barbarian influxes, was carried out with little democratic consent and with heated public debate suppressed.

Likewise, he diagnoses an institutional ideological illiteracy among modern leaders, an absence of grounding in Britain’s constitutional freedoms and culture, which has given rise to policies that mimic authoritarian control (akin to certain Chinese methods), yet lack any democratic justification; and astonishingly, the public has largely acquiesced.

Starkey also deplores a shameful erosion of national identity; citizenship now often amounts to nothing more than a piece of paper, divorced from the deeper bonds of birth, cultural lineage, or historical continuity.

Finally, he laments the state of public trust, describing the Britain of his youth: Peaceful, homogenous, high-trust, as having been deliberately dismantled by the legacy of 1990s-era policies.

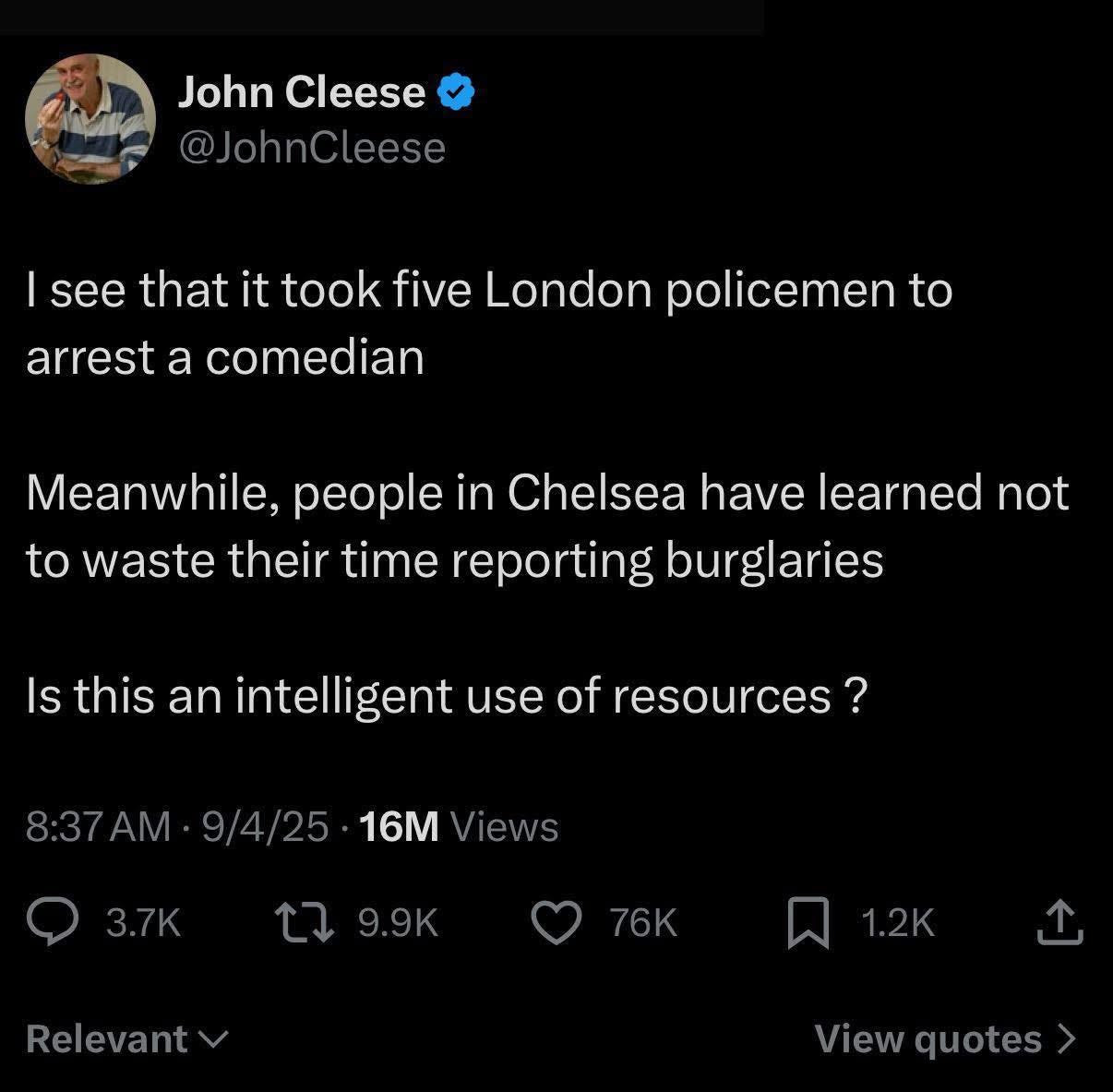

In this context, the arrest of Graham Linehan assumes a sharper, more alarming significance. The comedian behind Father Ted and The IT Crowd was detained at Heathrow by armed officers, hospitalised after the ordeal, and is now barred from posting on X. His arrest was triggered by three posts: one described male access to female-only spaces as abusive and ended with the hyperbolic suggestion that if all else failed such men should be “punched in the balls”; another mocked a transgender rally with the caption “a photo you can smell”; a third declared, “I hate them. Misogynists and homophobes. **** em.” The rhetoric was crude and, in the first case, could be construed as a call to violence, something Catholics must unequivocally reject. Yet the state’s response, armed arrest, bail conditions restricting speech, and parallel charges of harassment unrelated to those posts, risks criminalising speech in a way wholly disproportionate to any traditional notion of public order.

We must ask: Have we created a state that dispatches armed officers in response to political provocation? Are we living in a democracy that punishes dissent? Or merely the discomfort it causes? At the same time, the political foundations crumble. Labour governs with minimal popular support; the Conservatives are in free-fall. Public consent, as Starkey reminds us, has been gradually replaced by a technocratic class that rules without deep allegiance. Nigel Farage’s rising profile may be less of a remedy than a symptom, emerging from the void left by discredited, detached parties. Don’t get me wrong; I hope he is not, I hope he sorts this all out.

From a Catholic perspective, this moment demands clarity. Human dignity requires the freedom to speak truth, even when that truth wounds sensibilities. Yet in today’s Britain, legality is too often mistaken for morality. As we recently discussed with Brian Holdsworth, when a society is severed from objective truth, revealed by God and confirmed by reason, it drifts into believing that whatever the state permits is good, and whatever it forbids is evil. What better example of this than abortion?

Thomas Hobbes reduced morality to the will of the sovereign, while Jeremy Bentham collapsed it into the calculus of pleasure and pain. Both approaches strip law of its moral core, leaving it as a mere instrument of control. Jonathan Sacks, in Morality, offers a corrective: Law, he shows, depends on a prior moral ecology of trust, responsibility, and shared norms. If that ecology collapses, law cannot preserve freedom; it can only terrify or coerce. Even John Stuart Mill, no friend of religion, argued that liberty should only be curtailed to prevent real harm to others. To stretch “harm” so far as to include mere offence is to betray Mill’s own principle, reducing liberty to sentiment and law to censorship. Aquinas provides the deepest analysis: law is a rule of reason ordered to the common good, and when it ceases to be so, it is not law at all (lex iniusta non est lex). A society that mistakes legality for morality and offence for harm abandons reason itself and with reason lost, justice and freedom soon follow.

So the central question remains: Are words upheld as dangerous weapons, or recognised as the first stirrings of truth? In Christian history, offence often heralded transformation: Christ confronted corrupt powers; the Apostles turned the world upside down. To equate offence with violence is to risk silencing prophets. As Aquinas held, law must allow for the expression of error unless it clearly causes harm, anything less turns the state into a persecutor of thought.

Britain now stands at a crossroads. Its institutions are toothless, its laws stretched to breaking, and its police are deployed into cultural conflicts while serious crime goes neglected. Public trust is in free-fall, and Farage, for better or ill, rises in the vacuum. But the real crisis is not who leads; it is whether the nation can reclaim constitutional reason, freedom, and truth, or continue down the path to managerial authoritarianism, where control replaces consent, and speech becomes suspect.

Catholics should not hope for salvation by shifting political parties. We must insist on a public order rooted in conscience, justice, and the common good. We must remind our society that no government, however powerful, can subordinate truth or silence conscience. The arrest of Graham Linehan is more than a culture-war skirmish, it is a moment of reckoning. If mere words now merit armed intervention, how long before our own convictions are deemed intolerable?

Fantastic article Mark, it's hard to believe what is going on right now? It's as if people are being made an example of to control the masses? But by whom, and why? Who or what is engineering all this, and for what outcome?

Brilliant thanks Mark. We are sinking fast. All the words of wisdom come from historical figures.

Can the Reform Party drain the swamp. I Pray and hope. 🙏🏻