Hijacked Development

Rescuing Newman from Misuse in the Church’s Moral Crisis: By Stephen Morgan

The Rev Dr. STEPHEN MORGAN has been Rector (i.e. Vice-Chancellor or President) of the University of Saint Joseph Macao since 2020, where he is a Professor of Theology and Church History. The University of Saint Joseph is the only comprehensive Catholic university in China.

Originally serving in the Royal Navy, he later worked in taxation, banking and private equity in Hong Kong and the City of London. He was Oeconomus of the Diocese of Portsmouth from 2004 until 2018 and is a Permanent Deacon of that diocese.

He has been a member of the academic staff of the Maryvale Institute of Higher Religious Sciences since 2011.

In 2022 he was elected Vice President of the International Federation of Catholic Universities. He is also President of the Executive Secretariat of the Association of South East Asian Catholic Colleges and Universities.

He is a Fellow of the Royal Historical Society, the Royal Society of Arts and the Royal Asiatic Society.

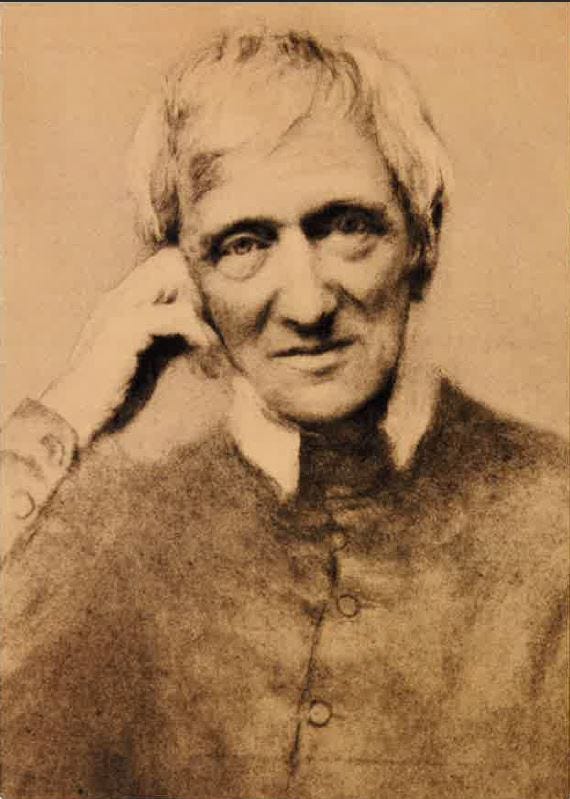

He is amongst the foremost Newman scholars in the world today. His outstanding book on Newman, "John Henry Newman and the Development of Doctrine", is available in paperback from Catholic University of America Press and Amazon in the UK and the US. I know just how invaluable this work is. I have read it. Stephen is my friend.

His book “John Henry Newman and the Development of Doctrine”, has been described as “The best work … on the development of Newman’s own thought on development of doctrine.”

I am so happy that he has agreed to write this outstanding article for CATHOLIC UNSCRIPTED, in which he demonstrates just how ridiculous it is to use the legacy of St. John Henry Cardinal Newman to mangle Catholic doctrine: I sincerely believe this short essay is, and will become, an essential reference tool for faithful clergy, academics and catechists who want to understand Newman’s thought and protect the Church from the wolves who want to ravage it. Enjoy!

In February 2023, the Anglican Archbishop of York, Stephen Cottrell, addressed the Church of England Synod with a bold theological claim. Seeking to justify the blessing of same-sex unions, he invoked St. John Henry Newman’s theory of doctrinal development to argue that revealed truth can change into its opposite. What was once considered sin could now, under the banner of “development,” be embraced as sacramentally significant.

The invocation was more than theologically strained—it was ironic. Newman had left Anglicanism precisely because his theory of development, written in the dying days of his life as an Anglican, but in fact worked out over the previous twelve years, demonstrated that the Church of England lacked doctrinal coherence, lacked the authority to validate the changes it had made to the Catholic and Apostolic faith. Yet today, even within the Catholic Church, Newman’s name is misused in precisely the same way: to provide theological cover for innovations that appear, under scrutiny, to contradict apostolic teaching.

Cardinal Víctor Manuel Fernández, Prefect of the Dicastery for the Doctrine of the Faith, has repeatedly cited Newman’s Essay on the Development of Christian Doctrine (1845) to defend controversial interpretations of documents such as Amoris Laetitia and Fiducia Supplicans. In both cases, Newman’s theory has been used to claim that the Church is not reversing her teachings but developing them—suggesting that it was possible to adapt pastoral practice while preserving doctrinal principle, as if the one does not act upon the other in the order of reality. Likewise, Cardinal Christoph Schönborn, entrusted by Pope Francis with the public presentation of Amoris Laetitia, spoke of a “real development” in moral theology, without explaining how a contradiction could be a development. More recently, Fiducia Supplicans, issued in December 2023, intensified the debate. By allowing the blessing of same-sex couples under specific non-liturgical circumstances, the declaration raised theological and pastoral alarms across the globe. Defenders again turned to Newman’s notion of development to justify the move as an evolution of pastoral care. But is this truly development—or doctrinal mutation disguised as mercy?

Such appeals to Newman are both theologically irresponsible and intellectually incoherent. Newman’s seven notes of what he called "authentic development" offer not a license for change, what he called "corruptions", but tools for discerning fidelity. Far from endorsing rupture, Newman defended the Church’s integrity and the continuity of her doctrine against those who, then as now, seek to remake the Church and her doctrine in the image of their own age. By applying Newman’s method rigorously, we can expose false developments, navigate confusion in the Church, and recover hope rooted in continuity, not novelty.

Newman’s Essay on Development, addressed what was then, as now, a pressing theological dilemma: how to account for the Church’s historical elaboration of doctrine without conceding to the Protestant accusation of innovation. He proposed that doctrine does develop—but in the way an acorn becomes an oak tree, the way a sping becomes a stream becomes a mighty river. True development preserves identity; it does not abandon essence. To safeguard the difference between development and corruption, Newman established seven “notes” or tests:

Preservation of Type – the essential form of the doctrine must remain intact;

Continuity of Principles – developments must be rooted in long-standing theological foundations;

Power of Assimilation – new expressions must be harmonised without contradiction;

Logical Sequence – developments must arise naturally and rationally from previous doctrine;

Anticipation of Its Future – signs of the development should exist in earlier tradition;

Conservative Action on Its Past – developments should protect and deepen earlier teaching;

Chronic Vigor – the development must bear fruit over time, not provoke decay or confusion.

These notes reflect a theology of faithful growth. Newman was no liberal. He opposed theological innovation untethered from the apostolic deposit and submitted his own work to the scrutiny of ecclesial authority. His theory was designed to defend the Church’s doctrinal credibility—not to rationalize doctrinal innovation.

Despite the clarity of Newman’s method, recent years have seen it misappropriated by those seeking to justify changes that clearly fail his tests. Archbishop Cottrell’s misuse of Newman in 2023 is a textbook example of distortion. By suggesting that the Church can develop doctrine to bless what Scripture and the Tradition consistently condemns, Cottrell departs from every one of Newman’s seven notes. There is no preservation of type, no continuity of principles, and certainly no conservative action upon the past. Instead, we find a reversal, justified by emotional appeal and cultural accommodation. Such appeals mark not continuity but permutatio—Newman’s own word for corruption of doctrine. The misuse is particularly offensive because it both seeks to endorse grave moral evil and leverages Newman’s authority to undermine the very tradition to which the end point that the logic of the Essay on Development: conversion to Catholicism at immense personal cost.

The 2016 apostolic exhortation Amoris Laetitia introduced the idea that, under certain conditions, divorced and civilly remarried Catholics might receive the Eucharist without annulment or the promise of continence. Cardinal Fernández has presented this not as a rupture, but as a pastoral development. Yet the move stands in direct tension with Pope John Paul II's Familiaris Consortio (1981), which reaffirmed the requirement of continence for such couples in the absence of a decree of nullity. Measured against Newman’s notes, the claim here of development collapses:

Preservation of Type: The sacrament of marriage and its indissolubility are placed in jeopardy.

Continuity of Principles: The principle of objective moral order in reception of the sacraments is loosened.

Conservative Action: There is none. Instead, Amoris softens or nullifies the previous standard.

Chronic Vigor: Far from stability, we see widespread confusion and division among bishops’ conferences.

A true development builds on what came before without undermining it. This is not what Amoris Laetitia does.

The 2023 declaration Fiducia Supplicans intensified this misuse. It permits blessings for same-sex couples, provided the blessing is “not ritualised” and not understood as an endorsement of the relationship itself. Once again, Fernández and others have presented this as a development of pastoral care. But despite its denials, the move has been received worldwide—particularly in Western media—as a soft endorsement of same-sex unions.

Measured by Newman’s criteria:

Preservation of Type: The Church’s practice of blessing has always signified approval of the object being blessed (e.g., homes, meals, marriages). This is not preserved.

Continuity of Principles: Traditional moral teaching affirms that homosexual acts are intrinsically disordered. Blessing a same-sex couple in a romantic union implies contradiction.

Power of Assimilation: The new practice is not assimilated but disruptive. It has led to global backlash, especially from African bishops.

Conservative Action: Rather than conserving doctrine, the declaration undermines clarity by introducing ambiguity.

Chronic Vigor: The declaration has caused division and confusion—not the signs of vitality Newman demands.

While Fernández insists that Fiducia Supplicans does not change doctrine, the shift in practice obscures and effectively revises the Church’s moral witness. This is precisely the kind of contradiction Newman sought to guard against. The idea that endorsed or tolerated practice changes, over time, the perception of doctrine is not simply a Marxist notion (although it certainly is that): it goes back to Aristotle.

Pope Leo XIV’s announcement of the forthcoming declaration of St John Henry Newman as a Doctor of the Church has been welcomed by many faithful Catholics. Yet, as noted a recent Substack article by Big Modernism; “The Consolidator,” it can, in the wrong hands (and there are plenty of those abroad in the contemporary Church), serve a strategic function: to sanctify Newman as a theological enabler of change. By citing Newman while advancing initiatives that Newman himself would have rejected, risks weaponising a misunderstood saint.

The July 2025 firings of theologians Ralph Martin, and Eduardo Echeverria, and the Canonist Edward Peters—each of whom had publicly criticized Amoris Laetitia or Fiducia Supplicans—underscore this concern. Notably, Echeverria, a respected Newman scholar, had used Newman’s seven notes to argue that these documents constituted reversals, not developments. The message is clear: fidelity to Newman’s actual method may now be career-ending in some theological circles.

The progressive appeal to Newman in justifying such innovations constitutes both a betrayal of his intent and a reversal of his method. Newman did not write to endorse theological innovation. He wrote to show how the Church could remain faithful amid historical elaboration. He did not see development as arbitrary evolution, but as guided by the Holy Spirit through the Magisterium. His writings were always submitted to ecclesial judgment. To cite him in defense of ambiguous pastoral practices that contradict previous magisterial documents is to repurpose him beyond recognition.

The original purpose of Newman’s Essay was to demonstrate Catholicism’s consistency with apostolic faith. Today, that same essay is cited to justify inconsistencies. The difference could not be starker. Newman offered a grammar of development—what is now being practiced is a rhetoric of change. Whether applied to Amoris Laetitia or Fiducia Supplicans, Newman’s seven notes expose fatal inconsistencies. These documents do not exhibit logical sequence or preserve doctrinal type. They do not deepen tradition but relativise it. They do not foster chronic vigor but sow division and mistrust. For many Catholics, especially those committed to the Church’s perennial moral teaching, the result is a crisis of confidence. Doctrinal instability fosters spiritual confusion and ecclesial alienation. The misuse of Newman only worsens the problem, replacing the hard task of discernment with the soft seduction of novelty.

The solution is not to discard Newman, but to reclaim him—faithfully and rigorously. Newman’s seven notes provide a precise framework for assessing whether proposed developments align with the Church’s tradition. They empower the faithful to assess teachings without relying on slogans or sentiment. Acknowledging ecclesial crisis is not despair—it is realism. Newman, no stranger to controversy, offers us a disciplined, sober way forward. His criteria protect against false developments while remaining open to true growth. This is not a call to nostalgia but to theological integrity.

The progressive misuse of Newman threatens to turn one of the Church’s most faithful theologians into a mascot for change he would never have endorsed. His theory of development, properly understood, offers a bulwark against rupture, not a pathway to it.

In declaring him a Doctor of the Church, Pope Leo XIV has rightly recognized Newman’s genius. But that genius must be honoured with fidelity, not reinterpreted beyond recognition. If the Church is to remain credible in the eyes of the faithful and the world, it must cease weaponising Newman’s name and begin applying his method.

Let Newman’s seven notes be our measure. Let them guide bishops, theologians, and laity alike through this time of confusion. In doing so, we may yet find clarity, unity, and renewal—not through rupture, but through faithful development. We should always remember that Newman's oft quoted "to live is to change and to be perfect is to have changed often" is immediately followed by "It (Christian doctrine) changes to remain the same." What was adultery yesterday is adultery today, what was fornication or sodomy or sacrilege yesterday is fornication or sodomy or sacrilege today. Misappropriating and misusing Newman, as if citing his name and the words "development of doctrine" can act like a stamp in a passport, granting a laissez passer to sin and error as if evil can thus be made good, untruth made truth, is to do violence to this great saint, this great soon-to-be Doctor of the Catholic Church.

More from Dr. Morgan on St. John Henry Newman:

This is such a timely article for me Mark, and I loved it. My late father was a big Newman fan, and as they say locally-"as the auld cock crows, the young one learns". Just today, at our local TLM the sermon was about continuity of tradition, and the priest was criticising, or maybe a better word would be questioning Pope Leo's proposal of Cardinal Newman as a Doctor of the Church, saying that he (Newman) was a proponent of theological development. While knowing that that was unlikely to be the case, I hadn't the facts and knowledge to coherently deal with what I knew could not be correct. Sorted. I'm so grateful.

I entered the Catholic Church last Easter after fifty years an evangelical. Although I didn’t know much about him, I chose John Henry Newman as my confirmation name based primarily on the fact he converted from Anglicanism, as did I. I now believe it was not my decision alone. God was at work. The more I learn of the man and his teachings, the more I realize that if I had known him thoroughly beforehand, Newman is the saint I would have chosen. Praise be to God and His unfathomable ways.