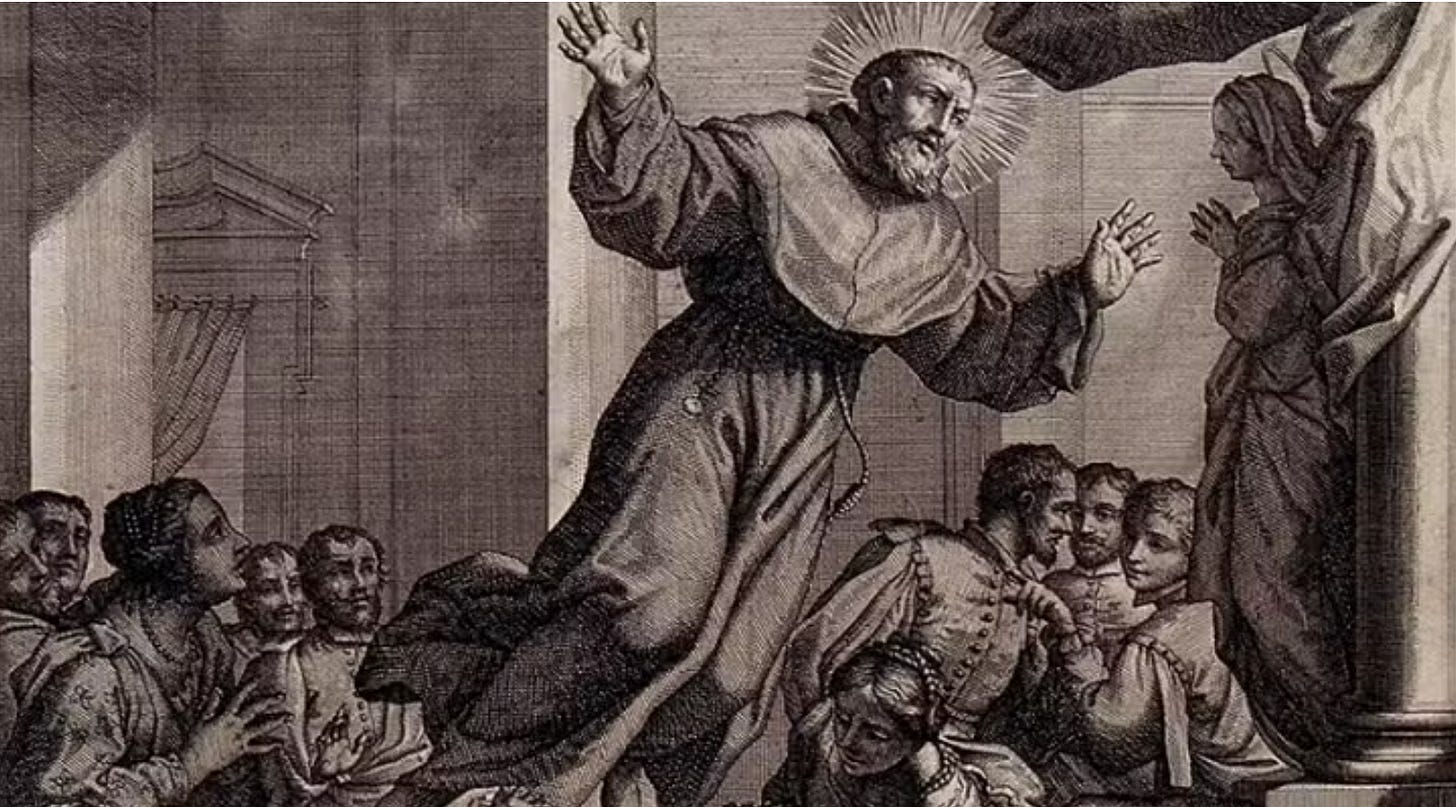

Holy Floater St Joseph of Cupertino

St Joseph’s life was one long succession of ecstasies, miracles of healing and supernatural happenings on a scale not paralleled in the reasonably authenticated life of any other saint

18th September ST JOSEPH OF CUPERTINO (A.D. 1663)

Joseph Desa was born June 17, 1603, at Cupertino, a small village between Brindisi and Otranto. His parents were poor and unfortunate. Joseph himself was born in a shed at the back of the house, because his father, a carpenter, was unable to pay his debts and the home was being sold up. His childhood was unhappy. His widowed mother looked on him as a nuisance and a burden, and treated him with great severity, and he developed an extreme absent-mindedness and inertia. He would forget his meals, and when reminded of them say simply, “I forgot”, and wander open-mouthed in an aimless way about the village so that he earned the nick-name of “Boccaperta”, the gaper. He had a hot temper, which made him more unpopular, but was exemplary and even precocious in his religious duties.

When the time came for him to try and earn his own living, Joseph was bound apprentice to a shoemaker, which trade he applied himself to for some time, but without any success. When he was seventeen he presented himself to be received amongst the Conventual Franciscans, but they refused to have him. Then he went to the Capuchins, and they took him as a lay-brother; but after eight months he was dismissed as unequal to the duties of the order: his clumsiness and preoccupation made him an apparently impossible subject, for he dropped piles of plates and dishes on the refectory floor, forgot to do things he was told, and could not be trusted even to make up the kitchen fire. Joseph then turned for help to a wealthy uncle, who curtly refused to aid an obvious good-for-nothing, and the young man returned home in despair and misery. His mother was not at all pleased to see him on her hands again and used her influence with her brother, a Conventual Franciscan, to have him accepted by the friars of his order at Grottella as a servant. He was given a tertiary habit and put to work in the stables. Now a change seems to have come over Joseph; at any rate he was more successful in his duties, and his humility, his sweetness, his love of mortification and penance gained him so much regard that in 1625 it was resolved he should be admitted amongst the religious of the choir, that he might qualify himself for holy orders.

Joseph therefore began his novitiate, and his virtues rendered him an object of admiration; but his lack of progress in studies was also remarked. Try as he would, the extent of his human accomplishments was to read badly and to write worse. He had no gift of eloquence or for exposition, the one text on which he had something to say being, “Blessed is the womb that bore thee”. When he came up for examination for the diaconate the bishop opened the gospels at random and his eye fell on that text: he asked Brother Joseph to expound it, which he did well. When it was a question of the priesthood, the first candidates were satisfactory that the remainder, Joseph among them, were passed without examination. After having received the priesthood in 1628 he passed five years without tasting bread or wine, and the herbs he ate on Fridays were so distasteful that only himself could use them. His fast in Lent was so rigorous that he took no nourishment except on Thursdays and Sundays, and he spent the hours devoted to manual work in those simple household and routine duties which he knew were, humanly speaking, all he was fitted to undertake.

From the time of his ordination St Joseph’s life was one long succession of ecstasies, miracles of healing and supernatural happenings on a scale not paralleled in the reasonably authenticated life of any other saint. Anything that in any way could be particularly referred to God or the mysteries of religion was liable to ravish him from his senses and make him oblivious to what was going on around him; the absent-mindedness and abstraction of his childhood now had an end and a purpose clearly seen. The sight of a lamb in the garden of the Capuchins at Fossombrone caused him to be lost in contemplation of the spotless Lamb of God and, it is said, be caught up into the air with the animal in his arms. He had a command over beasts surpassing that of St Francis himself; at all times he said to gather round him and listen to his prayers, a sparrow at a convent came and went at his word. Especially during Mass or the Divine Office he would be lifted off his feet in rapture. During the seventeen years he remained at Grottella over seventy occasions are recorded of his levitation, the most marvellous being when the friars were building a calvary. The middle cross of the group was thirty-six feet high and correspondingly heavy, defying the efforts of ten men to lift it. St Joseph is said to have “flown” seventy yards from the door of the house to the cross, picked it up in his arms “as if it were a straw”, and deposited it in its place. This staggering feat is not attested by an eye-witness, and, in common with most of his earlier marvels, was recorded only after his death, when plenty of time had elapsed in which events could be exaggerated and legends arise. But, whatever their exact nature and extent, the daily life of St Joseph was surrounded by such disturbing phenomena that for thirty-five years he was not allowed to celebrate Mass in public, to keep choir, to take his meals with his brethren, or to attend processions and other public functions. Sometimes when he was bereft of his senses they would try to bring him to by hitting him, burning his flesh or pricking it with needles, but nothing had any effect except, it is said, the voice of his superior. When he did come back to himself he would laughingly apologize for what he called his “fits of giddiness”.

Levitation, the name given to the raising of the human body from the ground by no apparent physical force, is recorded in some form or other of over two hundred saints and holy persons (as well as of many others), and in their case is interpreted as a special mark of God’s favour whereby it is made evident even to the physical senses that prayer is a raising of the heart and mind to God. St Joseph of Cupertino, in both the extent and number of these experiences, provides the classical examples of levitation, for, if many of the earlier incidents are doubtful some of those recorded in his later years are very well attested. For example, one of his biographers states that: “When in 1645 the Spanish ambassador to the papal court, the High Admiral of Castile, passed through [Assisi] he visited Joseph of Cupertino in his cell. After conversing with him he returned to the church and told his wife: ‘I have seen and spoken with another St Francis.’ As his wife then expressed a great desire to enjoy the same privilege, the father guardian gave Joseph an order to go down to the church and speak with her Excellency. To this he made answer: ‘I will obey, but I do not know whether I shall be able to speak with her.’ In point of fact no sooner had he entered the church than his eyes rested on a statue of Mary Immaculate which stood over the altar, and he at once flew about a dozen paces over the heads of those present to the foot of the statue. Then after paying homage there for some short space and uttering his customary shrill cry he flew back again and straightway returned to his cell, leaving the admiral, his wife, and the large retinue which attended them, speechless with astonishment.” This story is supported in two biographies by copious references to depositions, in the process of canonization, of witnesses who are expressly stated to have been present.

“Still more trustworthy,” says Father Thurston in the Month for May 1919, “is the evidence given of the saint’s levitations at Osimo, where he spent the last six years of his life. There his fellow religious saw him fly up seven or eight feet into the air to kiss the statue of the infant Jesus which stood over the altar, and they told how he carried off this wax image in his arms and floated about with it in his cell in every conceivable attitude. On one occasion during these last years of his life he caught up another friar in his flight and carried him some distance round the room, and this indeed he is stated to have done on several previous occasions. In the very last Mass which he celebrated, on the festival of the Assumption 1663, a month before his death, he was lifted up in a longer rapture than usual. For these facts we have the evidence of several eye-witnesses who made their depositions, as usual under oath, only four or five years later. It seems very difficult to believe that they could possibly be deceived as to the broad fact that the saint did float in the air, as they were convinced they had seen him do, under every possible variety of conditions and surroundings.” Prosper Lambertini, afterwards Pope Benedict XIV, the supreme authority on evidence and procedure in canonization causes, personally studied all the details of the case of St Joseph of Cupertino. The writer goes on: “When the cause came up for discussion before the Congregation of Rites [Lambertini] was ‘promotor Fidei’ (popularly known as the Devil’s Advocate), and his ‘animadversions’ upon the evidence submitted are said to have been of a most searching character. None the less we must believe that these criticisms were answered to his own complete satisfaction, for not only was it in his great work, published in 1753 the decree of beatification, but in that, when pope, he speaks as follows: ‘Whilst I discharged the office of promoter of the Faith the cause of the venerable servant of God, Joseph De Servorum Dei Beatificatione, etc., the cause of the venerable servant of God, Joseph of Cupertino, came up for discussion in the Congregation of Sacred Rites, which after my retirement was brought to a favourable conclusion, and in this eyewitnesses of unchallengeable integrity gave evidence of the famous upliftings from the ground and prolonged flights of the aforesaid servant of God when rapt in ecstasy.” There can be no doubt that Benedict XIV, a critically-minded man, who knew the value of evidence and who had studied the original depositions as probably no one else had studied them, believed that the witnesses of St Joseph’s levitations had really seen what they professed to have seen.”

There were not wanting persons to whom these manifestations were a stone of offence, and when St Joseph attracted crowds about him as he travelled in the province of Bari, he was denounced as “one who runs about these provinces and as a new Messias draws crowds after him by the prodigies wrought on some few of the ignorant people, who are ready to believe anything”. The vicar general carried the complaint to the inquisitors of Naples, and Joseph was ordered to appear. The heads of his accusation being examined, the inquisitors could find nothing worthy of censure, but did not discharge him; instead they sent him to Rome to his minister general, who received him at first with harshness, but became impressed by St Joseph’s innocent and humble bearing and he took him to see the pope, Urban VIII. The saint went into ecstasy at the sight of the vicar of Christ, and Urban declared that if Joseph should die before himself he would give evidence of the miracle to which he had been a witness. It was decided to send Joseph to Assisi, where again he was treated by his superiors with considerable severity, they at least pretending to regard him as a hypocrite. He arrived at Assisi in 1639, and remained there thirteen years. At first he suffered many trials, both interior and exterior. God seemed to have abandoned him; his religious exercises were accompanied with a spiritual dryness that afflicted him exceedingly and terrible temptations cast him into so deep a melancholy that he scarce dare lift up his eyes. The minister general, being informed, called him to Rome, and having kept him there three weeks he sent him back to Assisi. The saint on his way to Rome experienced a return of those heavenly consolations which had been withdrawn from him. Reports of Joseph’s holiness and miracles spread over the borders of Italy, and distinguished people, such as the Admiral of Castile mentioned above, would call at Assisi to visit him. Among them was John Frederick, Duke of Brunswick and Hanover. This prince, who was a Lutheran, was so struck with what he had seen that he embraced the Catholic faith. Joseph used to say to some scrupulous persons who came to consult him: “I like neither scruples nor melancholy; let your intention be right and fear not”, and he was always urging people to prayer. “Pray”, he would say, “pray. If you are troubled by dryness or distractions, just say an Our Father. Then you will be praying.” When Cardinal Lauria asked him what souls in ecstasy saw during their raptures he replied: “They feel as though they were taken into a wonderful gallery, shining with never-ending beauty, where in a glass, with a single look, they apprehend the marvellous vision which God is pleased to show them.” In the ordinary comings and goings of daily life he was so preoccupied with heavenly things that he departed at once—leaving his hat, his cloak, his breviary and his spectacles behind him. To prison, in effect, he had gone. He was not allowed to leave the convent enclosure, to speak to anyone but the friars, to write or to receive letters; he was completely cut off from the world. Apart from wondering why he should be sundered from his fellow Conventuals and treated like a criminal, this life must have been particularly satisfactory to St Joseph. But soon his whereabouts was discovered and pilgrims flocked to the place; whereupon he was spirited away to lead the same sort of life with the Capuchins of Fossombrone. The rest of his life was spent like this. When in 1655 the chapter general of the Conventual Franciscans asked for the return of their saint to Assisi, Pope Alexander VII replied that one St Francis at Assisi was enough, but in 1657 he was allowed to go to the Conventual house at Osimo. Here the seclusion was, however, even more strict, and only selected religious were allowed to visit him in his cell. But all this time, and till the end, supernatural manifestations were his daily portion: he was in effect deserted by man but God was ever more clearly with him. He fell sick on August 10, 1663, and knew that his end was at hand; five weeks later he died, at the age of sixty. He was canonized in 1767.

From Butler’s Lives of the Saints

Wonderful. Pray....that is good advice.

I know this is off topic, but I cannot find any place else to reach out to you guys even though I paid my yearly fee before you guy parted ways and switched to Substack.

Have you seen this:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kwk1weylwpw

In it Pope Lea says this about the subject of lgbtetc and changing Church doctrines:

at 2:15

"I think we have to change attitudes before we ever change doctrines" -----What is that!!! Who is "we'?

He says some other concerning things in this video as well.