Pilate’s Metaphysical Relativism and the Ontology of Truth

Augustine, Johannine Christology, and the Moral Economy of Speech

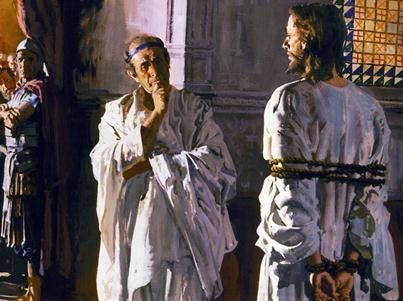

And Jesus answered “Just as you say, I am a king. For this I was born and for this I have come into the world, to bear witness to the truth. Everyone who is on the side of truth hears my voice.” Pilate said, “What is truth?”.

John 18: 37-38.

“Did you like the book and instruments that Uncle and I gave you?” said Aunt Emma brightly.

“No,” said William gloomily and truthfully. “I’m not int’rested in Church History an’ I’ve got something like those at school. Not that I’d want ‘em,” he added hastily, “if I hadn’t em.”

“William!” screamed Mrs. Brown in horror. “How can you be so ungrateful!”

“I’m not ungrateful,” explained William wearily. “I’m only being truthful...”

Richmal Crompton, “William’s Truthful Christmas”

John’s account of Pilate’s interaction with Jesus and therefore with God and with truth itself is read by some philosophers as an assertion of metaphysical relativism. These people are correct.

I say metaphysical because to think of him, as some do, as a prototype moral relativist doesn’t get to the depth of Pilate’s transgression. Morality is downstream from metaphysics (which itself is the story of God’s moment-by-moment recreation of everything from His position outside of time).

Pilate is not just a senior civil servant concerned with shoring up a fracturing civil order. His words make clear that his scepticism, or nihilism, is directed at the idea of truth itself.

For the religiously desensitised the Governor of Judea is a New Testament ironist, finding amused detachment in the ridiculousness of an unfolding and escalating doctrinal dispute, one of merely local significance.