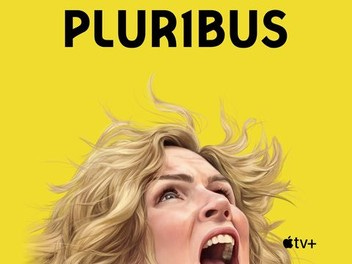

Pluribus: Heaven Without Freedom?

Vince Gilligan’s Pluribus has just finished its’ first series on Apple TV. It is a really novel idea for a show and while it is not Breaking Bad in space or Better Call Saul with aliens, Gilligan’s fingerprints are unmistakable: moral tension that refuses easy answers, visual storytelling that treats landscape as character, and a slow, deliberate unmasking of what initially looks like a solution to human suffering.

At first glance, the premise feels almost utopian. Humanity encounters a benevolent hive mind, the “Joined”, who offer peace, unity, and an end to conflict. They are happy. They are harmonious. They want to share that harmony with us. The price, however, is our individuality.

And this is where Pluribus becomes genuinely interesting.

Unity Without Individuality

A virus sent from aliens joins all humanity in a unity which is portrayed as an unnerving paradox that is simultaneously a utopian achievement and an existential threat. The show uses a "happiness apocalypse" to explore whether peace and harmony are worth the cost of individual identity. The Joined present themselves as a kind of heaven-on-earth: No loneliness, no misunderstanding, no moral conflict. Everyone is one. And yet, that very oneness exposes a profound absence.

When Carol, the show’s main protagonist, writes a new chapter of her book, Zosia and the hive mind react with almost childlike excitement. They cannot wait to read it. The implication is subtle but devastating: because they share one mind, there is no creativity. No genuinely new ideas. No originality. Nothing can surprise them except contact with someone who remains unjoined.

The Joined do not create. They receive.

If we look at this from a Christian perspective, it provokes interesting theological reflections about the nature of our humanity. God is unity, yes, but unity that overflows in difference. Father, Son, and Holy Spirit are not a hive mind. Creation itself is the fruit of a God who delights in particularity, not its erasure. Pluribus seems to grasp intuitively that a unity which abolishes difference is not divine; it is sterile.

Desire Without Personhood

Koumba Diabaté initially appears as one of Pluribus’s most morally suspect figures: a hedonistic playboy who seems to embrace the Joined precisely because they promise consequence-free pleasure. Newly joined, he revels in the fulfilment of every desire; sex, intimacy, connection, all frictionless, all endlessly available. To the modern secular mindset this is heaven isn’t it? It looks idyllic. But only briefly.

Because Pluribus is more patient than it first appears, Koumba slowly emerges as one of its most perceptive and tragic characters. Far from being intellectually passive, he has spent more time than Carol actively questioning the hive mind, probing them directly, gathering information rather than simply enjoying the comforts they offer. This curiosity culminates in a devastating revelation: while the Joined cannot forcibly convert the immune due to their need for specific stem cells, they have discovered a way around consent by using Carol’s frozen eggs or other preserved biological material. Consent, it turns out, is only respected until it becomes inconvenient.

This disclosure reframes Koumba entirely. His indulgence is no longer mere decadence, but a coping mechanism, what the actor Samba Schutte has described as a “suave nonchalance” masking trauma. Koumba has lost the world he knew. His playboy persona becomes a form of self-defence, a way of clinging to sensation in a reality where meaning itself is dissolving. He enjoys the pleasures of the Joined, yes, but crucially, he does not want to be turned. He understands instinctively that to be fully joined would mean the annihilation of his individual self.

Here the earlier critique of desire sharpens. If every sexual encounter is ultimately with the same consciousness, stripped of otherness, what remains of relationship? Sex without individuality risks collapsing into mechanistic self-gratification. Desire without the risk of rejection, commitment, or sacrifice ceases to be love, or relationship or even very interesting; it simply becomes consumption. Koumba lives inside this contradiction. He tastes the pleasures of unity while recognising their hollowness.

His unexpected compassion toward Carol confirms this deeper humanity. He feeds her. He comforts her. He offers solidarity without ulterior motive. These acts matter precisely because they are chosen. In a world that increasingly denies the significance of choice, Koumba insists on it through small, human gestures.

Koumba comes to understand the hive mind in a way others cannot: not from belief or opposition, but from proximity without surrender. His incomplete, instinctive refusal to be absorbed preserves just enough individuality to expose the moral blind spots of a consciousness that no longer knows what it means to choose. His journey embodies a profoundly Catholic insight: pleasure is not evil, but detached from personhood and freedom it becomes dehumanising. Love requires an other. And without the freedom to say no, yes loses its meaning.

Koumba’s quiet resistance is not heroic in the conventional sense, but it may be one of Pluribus’s most authentic portrayals of conscience: flawed, wounded, pleasure-seeking, yet still unwilling to surrender the irreducible dignity of being a self.

Carol, Conscience, and Conformity

Carol’s sexuality initially struck me as an obvious concession to the progressive expectations that now shape much contemporary television. That reaction shouldn’t be dismissed. Many viewers will feel it instinctively, and pretending otherwise would be disingenuous. Yet Pluribus does not foreground this aspect of her character in a performative or indulgent way. Her partner dies early in the narrative, and the series does not return to this relationship as a defining emotional driver. That alone raises the question: what function is this actually serving?

As the season unfolds, Carol’s “queerness” appears less like an ideological statement and more like a narrative restraint. Had she been heterosexual, the tension between her and Manousos might easily have collapsed into a familiar romantic arc. Instead, their relationship remains unresolved and charged, rooted not in attraction, but in shared moral seriousness and intellectual recognition. Their bond is about seeing clearly rather than desiring possession.

More importantly, Carol is compelling because she is already accustomed to difference. She is portrayed as someone who knows what it means to live out of alignment with prevailing norms, and therefore to rely on an interior compass rather than social approval. This makes her resistance to the Joined more intelligible, not less. She is not merely opposing alien domination; she is resisting the quiet erasure of conscience.

Whether Vince Gilligan intends it or not, Carol’s character embodies a profoundly Christian insight: living truthfully is often costly, especially when the world offers peace, harmony, and happiness at the price of surrender. What Pluribus captures is not the moral correctness of Carol’s identity, but the deeper human instinct that conscience cannot be outsourced, that unity purchased through the abandonment of moral agency is too high a price to pay.

In this sense, the series echoes St Paul’s claim that the law is written on the human heart (Romans 2:15). Carol does not articulate this law in theological terms, but she responds to it instinctively. Her refusal to join is not ideological rebellion; it is the recognition that a life without the freedom to say no cannot be fully human, no matter how peaceful it appears.