The Epiphany of Our Lord Jesus Christ

The whole nation of the Jews on account of Jacob’s and Daniel’s prophecies was in expectation of the Messiah’s appearance among them

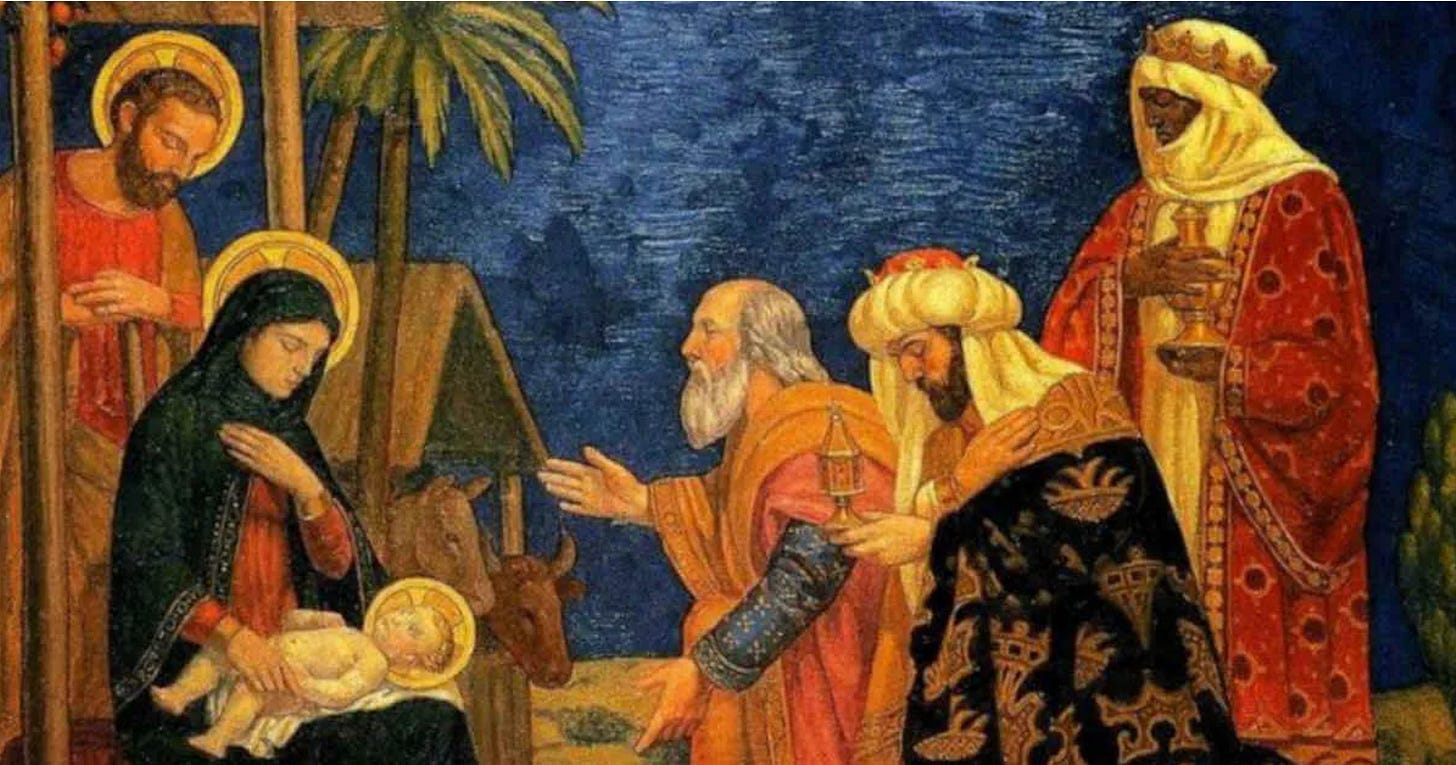

EPIPHANY, which in Greek signifies appearance or manifestation, is a festival principally solemnised in honour of the revelation Jesus Christ made of Himself to the Magi, or wise men ; who, soon after His birth, by a particular inspiration of Almighty God, came to worship Him and bring Him presents. Two other manifestations of our Lord are jointly commemorated on this day in the office of the Church : that at His baptism, when the Holy Ghost descended on Him in the visible form of a dove, and a voice from Heaven was heard at the same time : “ This is my beloved Son, in whom I am well pleased ; ” and that of His divine power at the doing of His first miracle, the changing of water into wine at the marriage of Cana, by which He manifested His glory, and His disciples believed in Him. Upon all these accounts this festival lays claim to a more than ordinary regard and veneration ; but from none more than us Gentiles, who in the person of the wise men, our first-fruits and forerunners, were on this day called to the faith and worship of the true God.

The summons of the Gentiles to Bethlehem to pay homage to the world’s Redeemer was obeyed by several whom the Bible mentions under the name and title of Magi, or wise men ; but is silent as to their number. The general opinion, supported by the authority of St Leo, Caesarius, Bede and others, declares for three. However, the number was small in comparison with those many others who saw that star no less than the wise men, but paid no regard to it ; admiring, no doubt, its unusual brightness, but indifferent to its divine message, or hardening their hearts against any salutary impression, enslaved by their passions and self-love. Steadfast in the resolution of following the divine call and fearless of danger, the Magi inquire in Jerusalem with confidence and pursue their inquiry in the very court of Herod himself ; “ Where is He that is born King of the Jews ? ”

The whole nation of the Jews on account of Jacob’s and Daniel’s prophecies was in expectation of the Messiah’s appearance among them, and the circumstances having been also foretold, the wise men, by the interposition of Herod’s authority, quickly learned from the Sanhedrin, or great council of the Jews, that Bethlehem was the place which was to be honoured with His birth, as had been pointed out by the prophet Micheas many centuries before.

The wise men readily comply with the voice of the Sanhedrin, notwithstanding the little encouragement these Jewish leaders afford them by their own example to persist in their search : for not one single priest or scribe is disposed to bear them company in seeking after and paying homage to their own king. No sooner had they left Jerusalem but, to encourage their faith, God was pleased again to show them the star which they had seen in the East, and it continued to go before them till it conducted them to the very place where they were to see and worship their Saviour. The star, by ceasing to advance, tells them in its mute language, “Here shall you find the new-born King.” The holy men entered the poor place, rendered more glorious by this birth than the most stately palace in the universe; and finding the Child with His mother, they prostrate themselves, they worship Him, they pour forth their souls in His presence. St Leo thus extols their faith and devotion: “When a star had conducted them to worship Jesus, they did not find Him commanding devils or raising the dead or restoring sight to the blind or speech to the dumb, or employed in any power divine action; but a silent babe, dependent upon a mother’s care, giving no sign of power but exhibiting a miracle of humility.”

The Magi offer to Jesus as a token of homage the richest produce their countries afforded—gold, frankincense and myrrh. Gold, as an acknowledgement of His regal power; incense, as a confession of His Godhead; and myrrh, as a testimony that He was become man for the redemption of the world. But their far more acceptable presents were the dispositions they cherished in their souls: their fervent charity, signified by gold; their devotion, figured by frankincense; and the unreserved sacrifice of themselves, represented by myrrh.

The earliest mention of a Christian festival celebrated on January 6 seems to occur in the Stromata (i, 21) of Clement of Alexandria, who died before 216. He states that the gnostic sect of the Basilidians kept the commemoration of our Saviour’s baptism with great solemnity on dates held to correspond with the 10th and 6th of January respectively. The notice might seem of little importance were it not for the fact that in the course of the next two centuries there is abundant evidence that January 6 had come to be observed throughout the East as a festival of high importance, and was always closely associated with the baptism of our Lord. In a document known as the “Canons of Athanasius”, whose text may in substance belong to the time of St Athanasius, say A.D. 370, the writer recognizes only three great feasts in the year—Easter, Pentecost and the Epiphany. He directs that a bishop ought to gather the poor together on solemn occasions, notably upon “the great festival of the Lord” (Easter); Pentecost, “when the Holy Ghost came down upon the Church”; and “the feast of the Lord’s Epiphany, which was in the month Tubi, that is the feast of Baptism” (canon 16); and he specifies again in canon 66, “the feast of the Pasch, and the feast of the Pentecost and the feast of the Epiphany, which is the fifth day of the month Tubi.”

According to oriental ideas it was through the divine pronouncement “this is my beloved Son in whom I am well pleased” that the Saviour was first manifested to the great world of unbelievers. In the opinion of the Greek fathers, the Epiphany (ἐπιφάνεια, showing forth), which is also called θεοφάνεια (manifestation of the deity) and τὰ φῶτα (illumination), was identified primarily with the scenes beside the Jordan. St John Chrysostom, preaching at Antioch in 386, asks, “How does it happen that not the day on which our Lord was born, but that on which He was baptized, is called the Epiphany?” And then, after dwelling upon certain details of liturgical observance, particularly the blessing of water which the faithful took home with them and preserved for a twelvemonth—he seems to suggest that the fact of the water remaining sweet must be due to some miracle—the saint comes back to his own question: “We give”, he says, “the name Epiphany to the day of our Lord’s baptism, because He was not made manifest to all when He was born, but only when He was baptized; for until that time He was unknown to the people at large.” Similarly St Jerome, living near Jerusalem, testifies that in his time only one feast was kept there, that of January 6, to commemorate both the birth and the baptism of Jesus; nevertheless he declares that the idea of “showing forth” belonged not to His birth in the flesh, “for then He was hidden and not revealed”, but rather to the baptism in the Jordan, “when the heavens were opened upon Christ”.

With the exception, however, of Jerusalem, where the pilgrim lady, Etheria (c. 395), bears witness, like St Jerome, to the celebration of the birth of our Lord together with the Epiphany on one and the same day (January 6), the Western custom of honouring our Saviour’s birth separately on December 25 came into vogue in the course of the fourth century, and spread rapidly from Rome over all the Christian East. We learn from St Chrysostom that at Antioch December 25 was observed for the first time as a feast somewhere about 376. Two or three years later the festival was adopted at Constantinople, and, as appears from the funeral discourse pronounced by St Gregory of Nyssa over his brother St Basil, Cappadocia followed suit at about the same period. On the other hand, the celebration of January 6, which undoubtedly had its origin in the East, and which from a reference in the passio of St Philip of Heraclea may perhaps already be recognized in Thrace at the beginning of the fourth century, seems by a sort of exchange to have been adopted in most Western lands before the death of St Augustine. It meets us first at Vienne in Gaul, where the pagan historian Ammianus Marcellinus, describing the Emperor Julian’s visit to one of the churches, refers to “the feast-day in January which Christians call the Epiphany”. St Augustine in his time makes it a matter of reproach against the Donatists that they had not adopted this newer feast of the Epiphany as the Catholics had done. We find the Epiphany in honour at Saragossa c. 380, and in 400 it is one of the days on which the circus games were prohibited.

Still, although the day fixed for the celebration was the same, the character of the Epiphany feast in East and West was different. In the East the baptism of our Lord, even down to the present time, is the motif almost exclusively emphasized, and the μέγας ἁγιασμός, or great blessing of the waters, on the morning of the Epiphany still continues to be one of the most striking features of the oriental ritual. In the West, on the other hand, ever since the time of St Augustine and St Leo the Great, many of whose sermons for this day are still preserved to us, the principal stress has been laid upon the journey and the gift-offerings of the Magi. The baptism of our Lord and the miracle of Cana in Galilee have also, no doubt from an early period, been included in the conception of the feast, but although we find clear references to these introduced by St Paulinus of Nola at the beginning of the fifth century, and by St Maximus of Turin a little later, into their interpretation of the solemnities of this day, no great prominence has ever been given in the Western church to any other feature but the revelation of our Lord to the Gentiles as represented by the coming of the Magi.

Taken from Butler’s Lives of the Saints