Thy Will be Done

Long before 3D printers could produce both tonight’s dinner and a set of deadly weapons, Giovanni Strazza created the translucent appearance of the Veiled Virgin out of marble

My dad is 91 and has lots of memories about life in the 1940’s and 1950’s, as well as an almost photographic memory of the various books he has read over the years about the rise and fall of kingdoms, about war, power, intrigue, deception. In the retelling of them, he weaves tales of real life in with the history books he’s read, such that I’m not sure if it is Eleanor of Aquitaine who is plotting to kill her husband or Mrs Craddock in the church choir.

But when it comes to my childhood, he remembers very little, except one particular memory which has clearly stayed with him. It is a memory of attending my swim lessons and watching me try and swim the backstroke. I would have been pre-school age. All of the other children stopped as soon as their face went under, he says; coming up spluttering and grabbing at the rail or holding on to one of the instructors. But as I swam, struggling to propel myself through the water, face dunking under at various points, I just kept going. I never dropped my feet, never held the rail, never panicked, and (despite the struggle) finally made it across the pool alone while the other children were all being aided by one of the instructors. “That tells you all you need to know about her character” my dad says, before saying something unflattering about a mule.

Before she died, my mum told me that my strong will was both a blessing and a curse, that it could lead to my damnation or to my salvation, depending on whether I ordered it towards God’s will, or not. I only came to see how true these words were much later on. For the 10 years following her death, that strong will led me away from God.

But a strong will is not an inherently bad thing. Fortitude is one of the four Cardinal Virtues, defined as the moral virtue that ensures firmness in difficulties and constancy in the pursuit of good. It involves both the ability to endure suffering and to attack evil or injustice. The vices which lie either side of Fortitude as a deficiency (lack of) or excess (too much) are cowardice and reckless behaviour, my own weakness is a propensity towards the vice of excess. A strong willed person whose will is misdirected, focuses on their own desires and has a hidden pride, relying on one’s own willpower, rather than the Grace of God. The ‘I don’t need any help’ taken to it’s extreme, includes no help from God too.

I learned the hard way (as many of you reading this may have done) that I needed God in all things. At first reluctantly, and then on my knees, I surrendered my will to His. But the will remains strong.

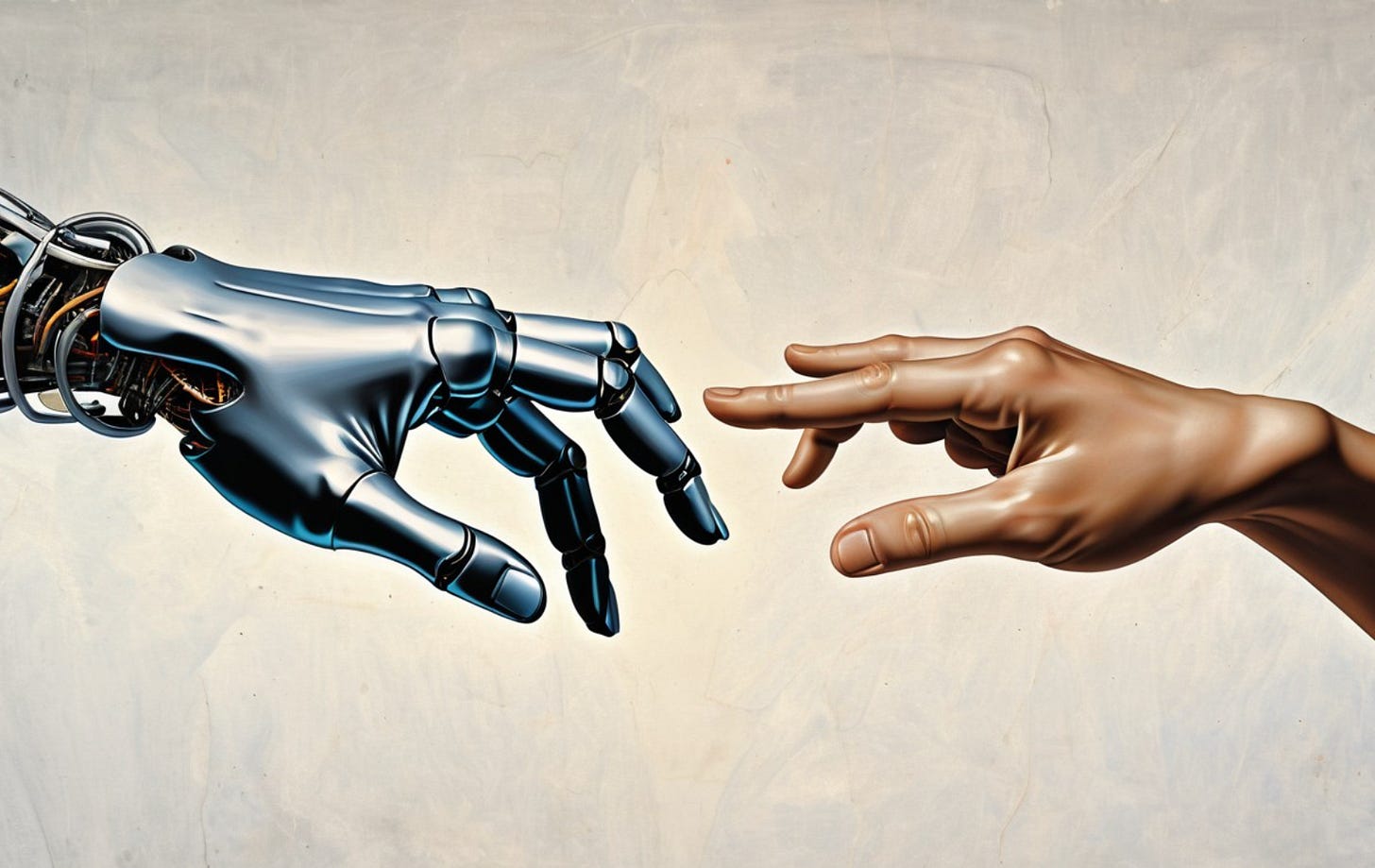

It is that same will, now surrendered, which wants to resist like billy-o the onslaught of AI. Just last week, Catholic apostolate Eternal Christendom released a statement outlining their commitment to delivering human generated content only. Their reasons are given here. This is a good start, and one that Catholic commentators everywhere should think seriously about following.

But why? What’s the harm?

To ask this is to begin with the assumption that avoidance of harm (or pain) is the motivating factor; the summum bonum, the highest good. It is a utilitarian starting point. If using AI makes life easier, gets things done more quickly and generates more income, then why not use it? We all have mouths to feed.

My objections are best raised as musings on the subject, rather than as a final judgement.

To being with, people are endlessly fascinating in a way that machines will never be. In an online world where everyone can find their own little subgroup of weirdness – who knew that there was more than one person in the world who liked reciting Proust, while jumping on a trampoline wearing nothing but mittens – each person is still unique and uniquely interesting. While queuing to board our plane to Florida recently, Mark and I stood behind a man trying desperately to explain time zones to the poor couple who had asked him a seemingly simple question. He stood before them like the Angel of the North, arms outstretched, saying ‘If you are in Glasgow, facing inverness then the time differential between you and your husband if he is in Bournemouth facing Cherbourg…’, I thought he was hilarious. “Why doesn’t he just say North and South?” Mark whispered exasperatedly.

I don’t know why this strange little man didn’t say North when he meant North, or why it takes some people 10 minutes to make the same point it takes another person two. I don’t know why my dad can remember what Queen Anne ate for breakfast, but little about my childhood, why my brother can climb mount Kilimanjaro but can’t walk around his own house on flat feet. We are all a bit weird. The deeper down you go, the less the ‘same’ you realise we are. This is not so with machines.

In ‘The Weight of Glory’ CS Lewis reminds us that there are no ordinary creatures

“It is a serious thing to live in a society of possible gods and goddesses, to remember that the dullest and most uninteresting person you talk to may one day be a creature which, if you saw it now, you would be strongly tempted to worship, or else a horror and a corruption such as you now meet, if at all, only in a nightmare. All day long we are, in some degree, helping each other to one or other of these destinations. It is in the light of these overwhelming possibilities, it is with the awe and the circumspection proper to them, that we should conduct all our dealings with one another, all friendships, all loves, all play, all politics. There are no ordinary people. You have never talked to a mere mortal. Nations, cultures, arts, civilisation—these are mortal, and their life is to ours as the life of a gnat. But it is immortals whom we joke with, work with, marry, snub, and exploit—immortal horrors or everlasting splendours. This does not mean that we are to be perpetually solemn. We must play. But our merriment must be of that kind (and it is, in fact, the merriest kind) which exists between people who have, from the outset, taken each other seriously—no flippancy, no superiority, no presumption. And our charity must be a real and costly love, with deep feeling for the sins in spite of which we love the sinner—no mere tolerance or indulgence which parodies love as flippancy parodies merriment. Next to the Blessed Sacrament itself, your neighbour is the holiest object presented to your senses. If he is your Christian neighbour he is holy in almost the same way, for in him also Christ vere latitat—the glorifier and the glorified, glory himself is truly hidden.”

Instinctively I feel that now, more than ever, we need persons, not machines. We must be cautious not to outsource anything that involves thought, wisdom, personality, emotions, convictions and prudence to AI. Grammar and spellchecks to detect errors are one thing, but having AI write entire sentences, paragraphs or even whole articles is another matter entirely. Especially when the writing is designed to persuade. We are persons, writing to other persons.

Those who rely on AI often defend its use by saying ‘But I agree with everything it’s saying, so why does it matter? It’s writing my conclusions, I’ve steered it’. In my view, this is the first step to our intellectual and emotional death, to the eradication of that which is unique, and even messy, about us. We give the world a version of us - yes, it’s me, but a polished, perfected version of me, like the girl who augments her breasts and has a facelift. First, we are the ones doing the thinking, but then gradually it’s ok that we aren’t the ones doing the thinking, as long as we ‘agree’ with what AI spits out. The next step thereafter is not difficult to foresee; we increasingly ‘clock out’ and become a drone as AI does it all for us. Many fret about things that will never happen,;aliens taking over the world, women priests, a zombie apocalypse, even as they gleefully succumb to the very real threat playing out before them threatening to strip them of their humanity.

I have written before about the technology around baby-making creating a Gattaca style world of Valids and Invalids. There are already some countries who have implemented screening programmes all but eliminating Down Syndrome from the population. And anyone who listened to Ross Douthat’s Interesting Times Podcast will have heard Noor Siddiqui discussing her work at Orchid technologies, whose aim is to create (for you) the perfect child, with the tagline ‘Have Healthy Babies’. She describes babymaking between a husband and wife as ‘the old fashioned way’ which she understands some people may still prefer…for now.

Whilst the dangers of this kind of artificial intrusion are obvious, the threat posed by AI is more subtle.

I have always loved words, I was never very good with numbers and still drive my loved ones mad when I begin an answer to a mathematical question with the word ‘…about’. It’s never ‘about’ in maths. Words are different. The choice of one word over another can make all the difference to the outcome, even when both are accurate descriptors, but this is a human judgement. Writers know that words have power and must be used responsibly. Carefully chosen and crafted words can be the difference between war and peace, and not just for Tolstoy.

In chapter 19 of John’s Gospel Jesus says to Pilate;

“You would have no power over me if it were not given to you from above”

We (especially Christian) writers might want to consider what ‘above’ we rely on in our craft. Do we ever want to be in a position where the following can be said?

“Your words would have no power over me were they not given to you from ChatGPT”.

Artists, at their best, reveal something of God in their work as grace builds on nature. Long before 3D printers could produce both tonight’s dinner and a set of deadly weapons at the push of a button, Giovanni Strazza could create the translucent appearance of the Veiled Virgin carved out of marble.

We don’t like to wait anymore. The law of supply and demand means that if we demand high quality faultless content regularly, we tempt the hand of those suppliers who know that they can fulfil the demands more easily with just a little help from dear old Grok. If Grok can help us to produce Strazza level content at 3D printing speed, it’s a no-brainer (literally).